“Americans should stop whining about food prices.”

That was the message AEI’s Mark J. Perry blasted last September to families gullible enough to believe that rising food prices were a problem:

It’s a favorite pastime in this country – Americans love to complain about rising food prices. Even when they aren’t. In fact, given all of the complaining you would never know that average food price inflation in recent years is actually the lowest in several generations. Below are three reasons that Americans should stop whining about food prices, and be a little more appreciative of how affordable food is in the US today, especially when compared to other countries, or when compared to previous decades in US history.

Perry’s three reasons for why American families should stop whining were that 1) Americans spend a smaller percentage of their budgets on food than they did 60 years ago, 2) people in other countries spend more of their money on food than we do, and 3) the four-year moving average of food inflation is low.

To which I say: so what? None of those supposedly devastating critiques of the “inflation is real crowd” came even close to addressing the real problem for millions of American families: namely, that the prices of stuff they buy are growing a lot more quickly than the wages they use to buy that stuff. Yes, it’s nice that we spend a smaller percentage of our budgets on food than other nations do or than our grandparents did after World War II, but that’s cold comfort to a working mom trying to figure out how to buy $20 worth of meat with only $15 left in her pockets.

A lot has happened since Perry told us ten months ago to stop whining. Did events prove him right or wrong? Was his inexplicably bizarre method of averaging four years’ worth of inflation data actually an effective way of predicting future price growth? Let’s take a look:

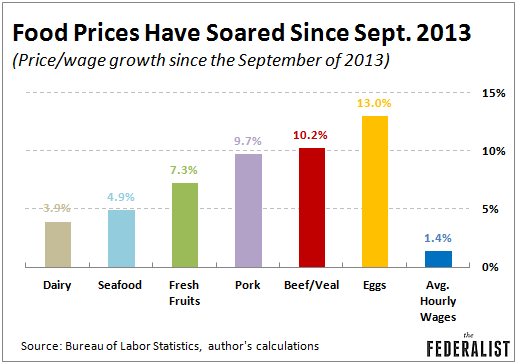

It turns out food prices have soared since he so confidently told us to shut up about them. The chart above shows the rapid disparity between food price growth and wage growth since Perry issued his “stop whining” directive. No joke: compared to less than a year ago, egg prices are up 13 percent. Beef is up 10 percent. Pork is up more than 9 percent. Fresh fruits are up over 7 percent. Overall, the prices of food at home are up 2.3 percent, while average hourly wages are up only 1.4 percent. In other words, food prices are growing 64 percent faster than wages.

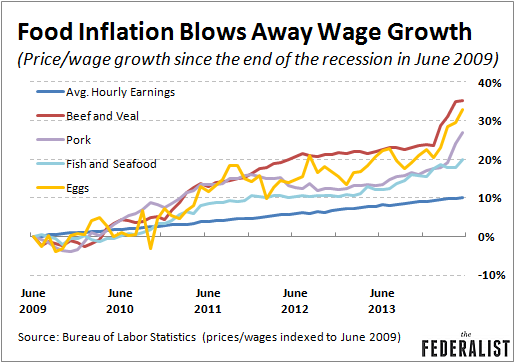

The overall trend since the end of the recession in June of 2009 is no different. Food price growth is outstripping wage growth:

Mark Perry is not alone in his skepticism, though. James Pethokoukis of AEI and Ramesh Ponnuru of National Review have also regularly belittled those with the audacity to look at rising price data and assume that prices are, in fact, rising, and that these rising prices might actually be causing problems for people. In his July 16 Bloomberg column in which he derisively referred to people concerned about inflation as “cranks,” Ponnuru wrote:

It’s certainly true that a looser monetary policy raises those prices and a tighter one would bring them down. But these policies would have the same effect on the price of labor. It’s the ratio of goods and prices to wages that matters for living standards. There’s no reason to think that the Fed’s policies are doing anything to increase the percentage of household budgets spent on food.

This is an interesting graf to unpack, especially since it attempts to make the same point as Perry did: that there’s no need to worry since the percentage of the household budget spent on food has remained relatively static. Here’s the thing, though: if food prices are growing more quickly than wages (and they are), and if families are still spending the same percentage of their money on food, then simple math says they must be buying less food. How is that a good thing, and why are we suddenly congratulating the Fed for it? At what point did our political pundit class decide that “Stop whining that you can’t afford more food for your family” or “Whatever, fatty, you didn’t need that food anyway” were winning messages?

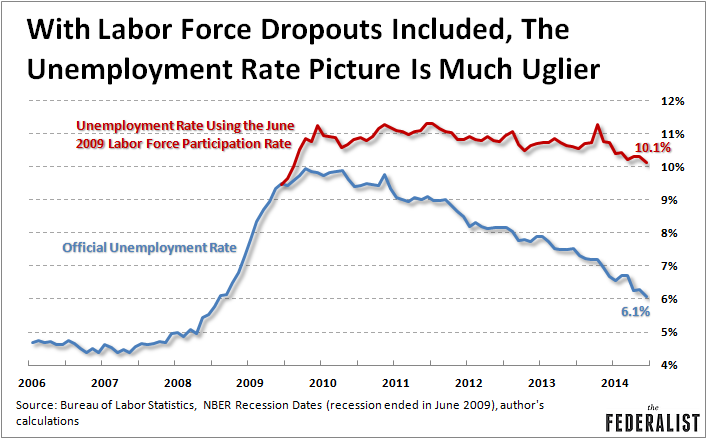

The assertion by Ponnuru that commodity inflation is only real if it simultaneously affects the price of labor is also odd. Unit labor costs are notoriously sticky. There’s no spot or futures market for labor, where if I don’t like the price of yesterday’s contract I can just sell it and buy a new one today. And a labor market where the true unemployment rate is closer to 10 percent than to 6 percent is not one that’s all that conducive to a rising unit cost of labor — when you’re lucky just to have a job, you’re not likely to march into your boss’s office and demand a raise every time new CPI data are released. Yes, the labor market is slowly improving, but we’re hardly at a point where employees are on equal ground with their employers when it comes time to bargain over compensation. Unfortunately, most employers are still price makers, and most employees are still price takers:

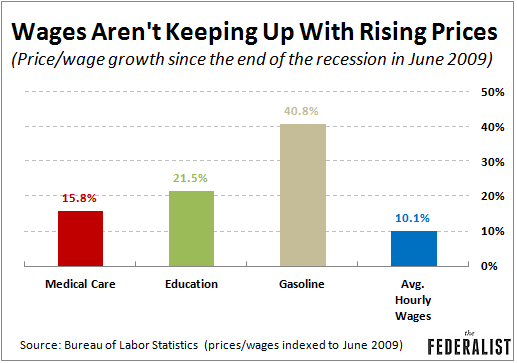

Ponnuru, to his credit, though, noted the real issue that matters the most to working families: the gap between wage and price growth. That’s a far more important measure than the array of irrelevant numbers thrown at the wall by Perry. What Ponnuru leaves unmentioned, though, is that in a number of major areas, prices are growing a heck of a lot faster than wages. Food price growth isn’t the only thing that’s outstripped wage growth. There has also been significant post-recession growth in the prices of education (not just college), medical care, and gasoline:

Those items comprise a pretty large share of the average family budget. According to the 2012 personal expenditure survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a married family with children will spend upwards of 27 percent of its annual budget on food, education, health care, and gas. Food alone, whether prepared at home or by a restaurant, eats up more than 13 percent of the average family’s budget each year.

Prices are rising, they’re rising faster than wages, and they’re rising for items that comprise a large chunk of the budgets of working American families. Those are facts. The question is what to do about those facts. The subtext to all of the inflation critiques from the likes of Perry, Pethokoukis, and Ponnuru is that we should leave the Federal Reserve alone. Stop blaming the Fed for inflation, you guys. Please ignore that QE, QE2, QE3, and a multi-year zero interest rate policy, etc. were all intentionally designed to increase inflation, you guys. Just ignore all the different goods for which prices are rising really rapidly, you guys. Ignore the fact that higher prices and middling wages are eroding standards of living, you guys.

Unfortunately, the constant Federal Reserve apologetics are seriously clouding these pundits’ collective judgment about an increasingly important political issue: whether America’s current political class has what it takes to make rising standards of living — rather than just rising prices — the norm for American families again. That is why families are so anxious today. They’re worried that the American dream is slipping away, and that only thing people in Washington and New York care about is protecting people in Washington and New York.

Guys, we get it. You like the Fed. A lot. That’s all fine and well: different strokes for different folks and all that. But stop letting your compulsion to defend the Fed prevent you from recognizing a very serious issue that’s affecting tens of millions of families. The first political party or ideology to come up with a coherent gas and groceries agenda for working families will have a huge advantage vs. a movement that decides its true constituency is a collection of technocrat bankers at the Fed.

The prices of things people buy are growing faster than many people’s ability to buy them. It’s time for pundits to stop pretending rapidly rising prices are no big deal.